I am frequently asked how to architect solutions when you have constraint/s which prevent you meeting requirements. It is not unusual for customers to have an expectation that they need and can get the equivalent of a Porsche 911 turbo for the price of a Toyota Corolla.

It’s also common for less experienced architects to focus straight away on budget constraints before going through a reasonable design phase and addressing requirements.

If you are constrained to the point you cannot afford a solution that comes close to meeting your requirements, the simple fact is, that customer is in pretty serious trouble no manner how you look at it. But this is rarely the case in my experience.

Typically customers simply need to sit down with an experienced architect and go through what business outcomes they want to achieve. Then the architect will ask a range of questions to help clarify the business goals and translate those into clearly defined Requirements.

I also find customers frequently think they need (or have been convinced by a vendor) that they need more than what they do to achieve the outcomes, e.g.: Thinking you need Active/Active datacenters with redundant 40Gb WAN links when all you need is VM High Availability and async rep to DR on 1Gb WAN links.

So my point here is always start with the following:

- Step 1: What is the business problem/s the customer is trying to solve.

Until the customer, VAR , Solution Architect and vendor/s understand this and it is clearly documented, do not proceed any further. Without this information, and a clear record of what needs to be achieved, the project will likely fail.

At this stage its important to also understand any constraints such as Project Timelines, CAPEX budget & OPEX budget.

- Step 2: Research potential solutions

Once you have a clear understanding of the problem, desired outcome / requirements, then its time for you to research (or engage a VAR to do this on your behalf) what potential products could provide a solution that addresses the business outcome, requirements etc.

- Step 3: Provide VAR and/or Vendors detailed business problem/s, requirements and constraints.

This is where the customer needs to take some responsibility. A VAR or Vendor who is kept in the dark is unlikely to be able to deliver anything close to the desired outcome. While customers don’t like to give out information such as budget, without it, it just creates more work for everyone, and ultimately drives up the cost to the VAR/vendor which in turn gets passed onto customers.

With a detailed understanding of the desired business outcomes, requirements and constraints the VAR/vendor should provide a high level indicative solution proposal with details on CAPEX and ideally OPEX to show a TCO.

In many cases the lowest CAPEX solution has the highest OPEX which can mean a significantly higher TCO.

- Step 4: Customer evaluates High level Solution Proposal/s

The point here is to validate if the proposed solution will provide the desired business outcome and if it can do so within the budget. At this stage it is importaint to understand how the solution meets/exceeds each requirement and being able to trace a design back to the business outcomes. This is why it’s critical to document the requirements so the high level design (and future detailed design) can address each criteria.

If the proposed solution/s do meet/exceed the business requirements, then the question is, Do they fall within the allocated budget?

If so, great! Choose your preferred vendor solution and proceed.

If not, then a proposal needs to be put to the business for additional budget. If that is approved, again great and you can proceed.

If additional CAPEX/OPEX cannot be obtained then this is where the balancing act really gets interesting and an experienced architect will be of great value.

- Step 5: Reviewing Business outcomes/requirements (and prioritise requirements!)

So lets say we have three requirements, R001, R002 and R003. All are importaint, but the simple fact at this point is the budget is insufficient to deliver them all.

This is where a good solution architect sets the customers expectations as a trusted adviser. The expectation needs to be clearly set that the budget is insufficient to deliver all the desired business outcomes and the priorities need to be set.

Sit with the customer and put all requirements into priority order, then its back and forth with the vendors to provide a lower cost (CAPEX/OPEX or both) detailing the requirement which have and have not been met and any/all implications.

In my opinion the key in these situations is not to just “buy the best you can” but to document in detail what can and cannot be achieved with detailed explanations on the implications. For example, an implication might be the RPO goes from 1hr to 8hrs and the RTO for a business critical application extended from 1hr to 4hrs. In day to day operations the customer would likely not know the difference, but if/when an outage occurred, they would know and need to be prepared. The cost of a single outage can in many cases cost much more than the solution itself, which is why its critical to document everything for the customer.

In my experience, where the implications are significant and clearly understood by the customer (at both a technical and business level), it is not uncommon for customers to revisit the budget and come up with additional funds for the project. It is the job of the Solution Architect (who should always be the customer advocate) to ensure the customer understands what the solution can/cannot deliver.

Where the customer understands the implications (a.k.a Risks), it is importaint that they sign off on the risks prior to going with a solution that does not meet all the desired outcomes. The risks should be clearly documented ideally with examples of what could happen in situations such as failure scenarios.

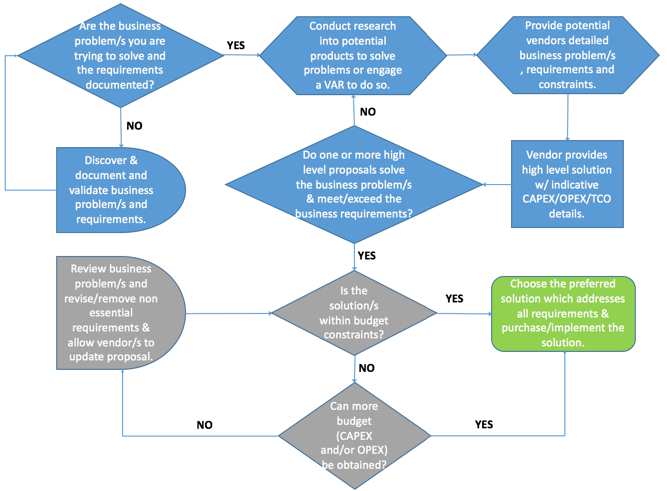

Basic Flowchart of the above described process:

The below is a basic flowchart showing a simplified process of gathering business requirements/outcomes through to an outcome.

Starting in the top left, we have the question “Are the business problem/s you are trying to solve and the requirements documented?

From there its a follow the bouncing ball until we come to the dreaded “Is the solution/s within the budget constraints?”. This area is coloured grey for a reason, as this is where the balancing act occurs and delays can happen as indicated with the following shape ![]() .

.

Once the customer fully understand what they are or are not getting AND IT IS FULLY DOCUMENTED, then and only then should a customer (or VAR/Architect recommend too) proceed with a proposal.

The above is not an exhausting process, but just something to inspire some thought next time you or your customers are constrained by budget.

Summary:

- Don’t just “Buy what you can afford and hope for the best”

- Document how requirements are (or are not) being met (That’s “Traceability” for all you VCDX/NPX candidates)

- Document any risks/implications and mitigation strategies

- Get sign off on any requirements which is not met

- Always provide a customer with options to choose from, don’t assume they wont invest more to address risks to the business

- If you can’t meet all requirements Day 1, ensure the design is scalable. A.k.a Start small and scale if/when required.

- Avoid low cost solutions that will likely end up having to be thrown out

Related Articles: